U.S. Border Patrol agent Saul Rocha navigates his Ford Explorer down a wide dirt road between two layers of fence that separate San Diego from Tijuana, Mexico. He points to patched holes in the steel wire mesh every few kilometres cut by illegal border-crossers using power saws, and a discarded homemade wire ladder curled at the base of the fence.

"They make them at home, they roll it up, they come, they jump the fence," he says of the ladders, which agents still regularly find scattered around the border.

Nine years ago, agents installed giant coils of barbed wire atop some stretches of fence to stop people from climbing over. But migrants quickly adapted by adding carpets and rope to their ladders to avoid the sharp barbs.

Yet patched holes and homemade ladders are among the few remaining obvious signs of illegal activity along this 106-kilometre stretch of the southwestern California border. What was once a place where hundreds of thousands of Mexican immigrants rushed past a chain-link fence from Tijuana every year, is now a bustling but orderly commercial neighbourhood.

The number of people caught crossing the San Diego border peaked in the mid-1980s. Back then, Border Patrol agents were catching 1,700 people a day. Today, as illegal immigration across the U.S. has plunged to 40-year lows, they are on track to average 77.

Driving past strip malls blasting Spanish-language radio, sprawling outlet stores selling Armani and Kate Spade, and massive shipping warehouses that surround San Diego's two border crossings – among the busiest in the world – the scene is of an orderly commercial and retail neighbourhood, much like those that dot the U.S.-Canadian border.

That is, until, Mr. Rocha pulls his vehicle in front of what we have come to see: eight sections of wall, nine metres tall, half of them constructed of concrete, the other half made of metal, and all towering higher than any barrier has ever been built along the U.S. border.

U.S. President Donald Trump made the promise of a "big, beautiful wall" with Mexico the centrepiece of his election campaign, reopening the bitter divide over the United States' relationship with its neighbour to the south. "We will, and must, build the Wall!" Mr. Trump tweeted Monday after a border patrol agent was killed and another wounded in a remote stretch of the Texas border.

By now, however, few people seem to expect a continuous wall with Mexico given the many billions it would take to construct such a barrier over terrain that includes towering cliffs, deep canyons and rivers. But the massive prototypes unveiled here late last month, standing sentinel over the most populated region of the U.S.-Mexico border, mark the latest chapter in a dramatic buildup of U.S. border security.

In the 30 years since the U.S. began building barriers along its 3,100-kilometre border with Mexico, the borderlands have served as the front-line defence against the war on drugs, and later the war on terror.

More recently, border security has become the United States' de facto immigration policy. Fears of a porous border have consistently derailed most bipartisan attempts at significant immigration reform even as the Border Patrol's budget has grown 10 times since 1993. In that time, the number of agents has grown 500 per cent and the U.S. has built nearly 1,100-kilometres of fencing.

Meanwhile, the number of people caught crossing the U.S. border from Mexico has plunged to levels not seen since the early 1970s. By most estimates, the undocumented population in the U.S. is actually shrinking as more Mexicans return home and fewer arrive.

Yet even as the U.S. has poured tens of billions of dollars into remaking its border with Mexico – and its current President is pushing to add billions more – Americans are no closer to feeling that their borders are secure.

"It's a mind over matter thing," said Doris Meissner, who served as Commissioner of the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service during the Clinton administration and is now a senior fellow at the Migration Policy Institute, an independent think tank. "So much of what immigration is about and so much of what the political pressure is about is not fact based, it's really emotional."

Borders, past and future: A visual guide

Eight prototypes of the Trump administration’s proposed border wall are on display near San Diego, along the most populous region of the U.S.-Mexico frontier.

GUILLERMO ARIAS/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

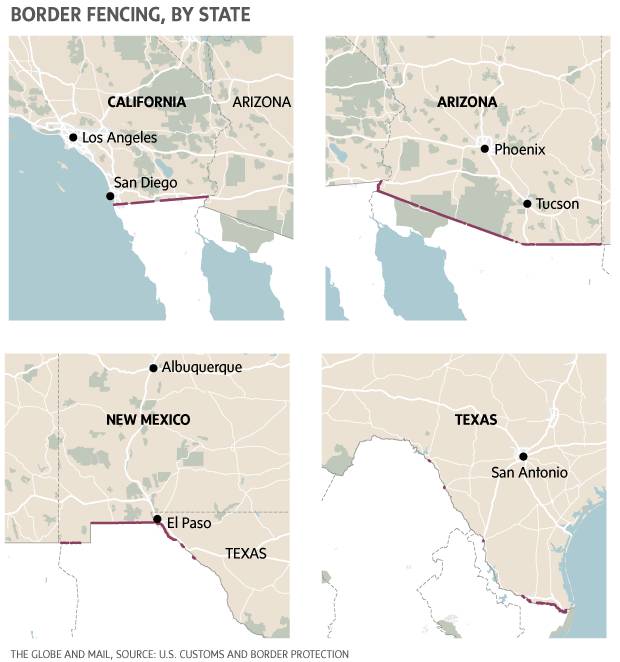

California, where U.S.-Mexico border fences first began to emerge, had an array of different types of fences.

U.S. CUSTOMS AND BORDER PROTECTION

How the border strategy has evolved

The first fencing went up along San Diego's Imperial Beach in 1990. That year, Border Patrol agents began welding 180,000 corrugated steel panels, three-metre-tall airstrip landing mats dating back to the Vietnam War that the agency got for free from the military, into 22-kilometres of fencing.

Agents in San Diego hoped the barrier would help them get a handle on what was then the main gateway for more than half of all the migrants trying to reach the U.S. "We would go in right at dusk and you would just see thousands of people just waiting for it to get dark," said Michael Fisher, who retired as head of the U.S. Border Patrol in 2015. "As soon as somebody blew the whistle, thousands of people would just start running across the border."

A 1993 study recommended the U.S. put up three layers of fencing along 145 kilometres of the border and expand highway checkpoints in more remote locations. But partly because of concerns over angering Mexico ahead of the launch of the North American free-trade agreement, little of the fencing was built.

Instead, the government focused its resources on San Diego and El Paso Tex. – where the vast majority of immigrants tried to cross the border illegally. They built fences, added new border agents and placed as many guards as they could as close to the border as possible.

Rather than concentrating on catching those who were already in the country, the prevailing border strategy in the 1980s, the show of force was meant to deter people from crossing in the first place. By targeting busy urban areas such as San Diego and Tijuana, collectively home to close to six million people, the government hoped to shift illegal crossings to more remote locations east of San Diego, where they would be easier to spot.

Over the next six years, apprehensions plunged in San Diego and El Paso. But they soared in the region around Tucson, reaching more than 600,000 by 2000, more than eight times what they had been just six years earlier. Border agents considered the idea of pushing people away from the city to rural locations to be a sign of success. But they were still overwhelmed by the number of migrants who opted to brave the punishing heat of Arizona's Sonoran Desert where summer temperatures can climb as high as 50 C.

"The cartels are always going to go where they make the most profit," said Eduardo Olmos, a border patrol agent in San Diego. "So if we have a lot of success here, they will move somewhere else."

As illegal migration soared in Arizona, so too did the number of people who died trying to cross the border. Migrant deaths skyrocketed from 72 in 1994 to 482 in 2005, most from exposure or drowning in the waters of the Rio Grande. Last year, an estimated 326 migrants died trying to cross the border, according to the International Organization for Migration, the United Nations' migration agency.

After the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, border security took on a new focus. Suddenly the major threat at the Mexican border wasn't drugs, or undocumented workers, it was terrorists.

The 2006 Secure Fence Act added more than 9,000 new border agents and mandated at least 1,100-kilometres of reinforced fencing along the border in a bid to plug holes where terrorists could slip through.

The number was derived partly from what border officials were asking for, but also from politicians who were looking for something to take back to their constituents heading into midterm elections.

"It was ultimately a political negotiation," Ms. Meissner said. "It did arise out of Border Patrol experience that this was about what they thought they needed. But it was also about what Congress thought it could do as a way of creating political cover for itself."

As of today, the border is nearly 68 kilometres shy of the 1,100 kilometres requirement, and roughly half of that is fencing made up of 1.5-metre-tall steel rails meant to stop vehicles, but not pedestrians.

Jan. 31, 2017: A U.S. border patrol agent patrols the border with Mexico in Nogales, Arizona. Illegal crossings in Arizona’s Sonoran Desert rose dramatically after crackdowns and fence-building in California and Texas. Scores of migrants died of exposure or drowning.

LUCY NICHOLSON/REUTERS

Barriers: How effective are they?

How well the soaring investment in border security – particularly in fences – worked to prevent illegal immigration remains a fierce political debate.

Border patrol officials are keen to emphasize that fences are just one element of border security and were never intended to completely seal the border, but rather to slow down crossers and make them easier to catch.

Still, it's clear that walls have worked in some areas. One 2011 study by the Department of Homeland Security found that apprehensions dropped 75 per cent in areas with fencing.

"When people say that fences don't work, they actually do," Mr. Fisher said. "When you're dealing with thousands and thousands of people trying to enter an open area, it slows them down."

Even so, he predicts that fewer than 160 kilometres of new fencing along the border will be built as the nine-metre wall championed by Mr. Trump. Instead, Mr. Fisher believes border security will increasingly rely on technology, such as fibre-optic cables buried in the ground along the border. Such technology, which has been used to help monitor oil pipelines, can act as an early warning system for border agents and costs a fraction of what has been tried in the past.

"The vast majority of the border with Mexico and Canada at some point is going to be technology," he said.

The U.S. government could go a long way toward improving border security just by completing the 1,100 kilometres of fencing proposed in the Secure Fence Act, said Ronald Colburn, a former national Deputy Border Patrol Chief. "Many of the things that were started nine or 10 years ago just need to be completed. That would help a lot."

Others say the buildup of fencing and manpower along the border has done little except to change where and how migrants cross the border and discouraged them from trying to go home again.

While the likelihood that someone would get caught crossing the border jumped as the U.S. has added more fences and border agents, virtually all of those who want to cross into the U.S. are ultimately successful, even if they have to try multiple times, said Princeton University professor Douglas Massey, who co-directs a project that surveys Mexican migrants.

Paid guides have turned to dangerous methods to smuggle people and drugs around the fencing, such as tunnels and ultralight aircraft, often used to deliver drugs. A rising number of illegal immigrants are showing up at official border entries with fake documents, or arriving by water.

"They'll try with jet skis, swimming , surfboards, boats," says Mr. Olmos the border agent in San Diego, where the border with Mexico stretches to the Pacific Ocean.

Academics who study Mexican migration say the steady buildup of manpower and fences along the border has little to do with the dramatic decline in people trying to cross the border illegally.

Combined, the number caught crossing illegally and estimates of those who successfully slipped into the U.S. have dropped from nearly 3.4 million in 2000 to fewer than 600,000 today. The Pew Research Center estimates the total undocumented population fell by roughly 1.4 million between 2007 and 2016 as more Mexicans returned home to the U.S. than arrived illegally.

Instead, researchers point to an array of economic and demographic factors that likely caused the drop.

The bursting of the housing bubble in 2008 hit immigrant-heavy industries, such as construction, especially hard. Since the financial crisis, Mexicans have opted to migrate to large cities within Mexico instead, said Wayne Cornelius, professor emeritus at the University of California, San Diego, and an expert in cross-border migration. "They seem to have had a positive experience, and with migration to a nearby city available to meet their economic needs, why spend thousands of dollars on a smuggler and run the physical risks of clandestine entry."

Those who are immigrating to the U.S. are doing so legally – the number who are in the U.S. on work visas has increased nearly five times in the past 20 years.

But the most significant factor behind falling illegal migration is Mexico's aging population. Fertility rates have declined dramatically since the 1970s, putting Mexico's population growth closely in line with the U.S. and other Western economies. Huge migration waves through the 1970s, 80s and 90s have emptied out communities that historically sent many residents to the U.S. for work, leaving a smaller pool of working-age men in Mexico to send abroad than in previous years.

Aurelia Lopez and her daughter, Antonia, look from Tijuana at the wall prototypes under construction in San Diego.

SANDY HUFFAKER/GETTY IMAGES

Changing demographics

As Mexican migration has fallen that has changed who is crossing the border, with significant implications for U.S. immigration policy.

In 2014 and again in 2016, Mexican migrants represented fewer than half of those caught at the border, outstripped by a surge of migrants fleeing gang violence in El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala. Many of those have been families and unaccompanied children who have crossed the Rio Grande into southeast Texas, which has become the new frontier of illegal immigration to the U.S.

Most come to seek asylum and turn themselves into border agents. The kind of quick-deportation procedures that are now the dominant policy along the U.S.-Mexico border typically don't apply to unaccompanied children and migrants with credible asylum claims, who are allowed to stay in the U.S. until their cases can be heard by an immigration judge.

"If you were really looking at the border holistically, from a broad policy perspective, the investment would not be going into 30-foot fences," Ms. Meissner said. "It would be going into immigration judges, immigration asylum officers, into efforts in Central America to stanch the smuggling of young people from that part of the world and obviously into supporting those governments to create more citizen security."

In the end, it may not matter what, if any, of Mr. Trump's vision for a wall with Mexico eventually materializes.

Apprehensions along the U.S.-Mexico border fell 30 per cent between Mr. Trump's inauguration in January and August, the most recent monthly figures, and appear to be on track to fall to new lows this year. Some border-wall advocates point out that Mr. Trump's anti-immigrant rhetoric alone may prove to be enough of a deterrent, though Prof. Cornelius says that argument ignores the long-term migration trends.

It's possible that Congress may hammer out a deal to fund at least some new fencing in exchange for legislative action to restore protections for recipients of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, the program that gave work permits to thousands of undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. as children, which Mr. Trump announced he would rescind.

And with illegal migration on track to fall to historic new lows this year, a political compromise that includes some more funding for the border – if not for a 3,100-kilometre wall – may just be enough for Mr. Trump to say he's kept his election promise, Ms. Meissner said. "Given the trends we're talking about, it gives the new administration the perfect formula for declaring victory and walking away from this whole project."

Others expect the disagreement over the border to continue to rage regardless of what gets built over the next three years. "Unfortunately without common sense being part of the equation, the political debate will again be part of the 2020 presidential elections," said Silvestre Reyes, a former border patrol chief in El Paso who served 16 years as a congressman and previously chaired the House intelligence committee. "Unfortunately, we just don't have the willingness to come to the table and realistically talk about a solution."

MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Trump’s border wall promise seeing first tangible signs